From the nostalgic beauty of analog photography to the cameras of the new iPhone 15, our relationship with photographs has changed drastically. By sharing our lives on social media, photography seems to have transformed into a collective practice more than an individual art form, causing an undeniable shift in its value.

The Barcelona-based collective Contrafotografía sees the problem not only in the oversaturation of images but also in the homogenization of the visual content we consume. Initiated by photographer and curator David Garcerán in 2018 to support the local punk scene in Barcelona, the non-profit, holocratic collective publishes alternative publications and zines on contemporary photography and counterculture, exploring our relationship with images in the context of new technologies, social media, and mass information. Their same-titled publication comes out at least two times a year, next to a smaller magazine titled “Roca Negra.” Despite being plugged into the local punk and photography scene, they expanded their international reach, collaborating with photographers from Mexico, France or the UK.

Since then, four more members have joined the collective: photographer and editor Antonia Valentina, fashion/product photographer and editor Diego Piqueras, creative director and designer Gonzalo Hergueta from Gonzalo Hergueta Studio, and graphic designer Marta Hernández currently working at Bureau Borsche.

In the following interview, we talked with the collective about their 11th issue of Contrafotografía called “Realismo Digital,” the DIY way of producing zines and the essence of punk. Let’s go!

You represent the self-publishing side of the market with more than affordable prices per copy. How do you distribute your issues?

We don’t see ourselves as part of a market since our products are sold only on our website and in stores or “distros” with which we share a personal connection, either by knowing the people behind them or through collaborations. The same applies to fairs. We distribute mainly through our website, but it feels too impersonal. These small fairs help a lot to meet people and create a community. Instead of the word “market” we would use “community” since there is no capital gain or capitalist intentions in anything we do. We just publish zines because we want to, when we want to, and where we want to. Right now, since the production costs are higher and we kept the prices of our publications low, we can only cover the cost of each issue after selling out.

The notion of punk is often actively reduced to a decorative selling point. What’s your perspective on that? How would you define a contemporary state of punk?

Punk does nothing by itself. Punk is reduced to something by those who are not involved in it. There’s a huge international DIY community working on diverse mutual aid projects, distribution networks of counter-cultural ideas, and political projects. Punk is part of that, another leg of that network strongly related to anarchism, squats, other sustainable housing projects, and all kinds of counter-cultural projects.

“Contrafotografía“ could be a perfect example of this, as a photography/editorial project related to all these things! The problem—and a good thing at the same time—is that the word “punk” evokes different associations depending on who you ask. A commercial music fest heavily exploiting its workers could be “punk” for many people based on its line-up. A band with a company in the background could be “punk” based on how music media and streaming services categorize them. We can easily find fashion companies saying they are punks because they “break the rules.”

From a personal point of view, our concept of punk is closely linked to anarchism. Maybe we have something in common with some people from these examples, but they mostly stand for everything we reject. It doesn’t mean we have the truth—but we use it to find our direction.

Could you describe the collaborative process behind each issue? What guides your curation and how do you interact with your contributors?

The project evolved very slowly. When Diego joined the project with the 9th issue, she brought in a new approach that is now our standard way of working. We choose a subject and do deep research on documentary photographic projects that would present a challenge to the readers. It’s a complex process of defining what to investigate, finding authors, and asking them to participate. After that, the final task of the editors is to set up a sequence of photos in a flat document. The positioning of all photographs within the magazine, the selection of works, and other details happen here. Then, the design team does their magic and makes this mess look amazing. At the same time, we have to request offers from diverse printing houses and send them the final design. Everyone who participates in this process is a collaborator, from the editor to the printer or the friends who distribute our zines.

We are currently working on new projects involving several meetings with authors, scanning old films, and reviewing hundreds of photo archives. We feel very lucky to now have a physical space for these meetings at Ateneu l’Harmonia in the neighborhood of Sant Andreu.

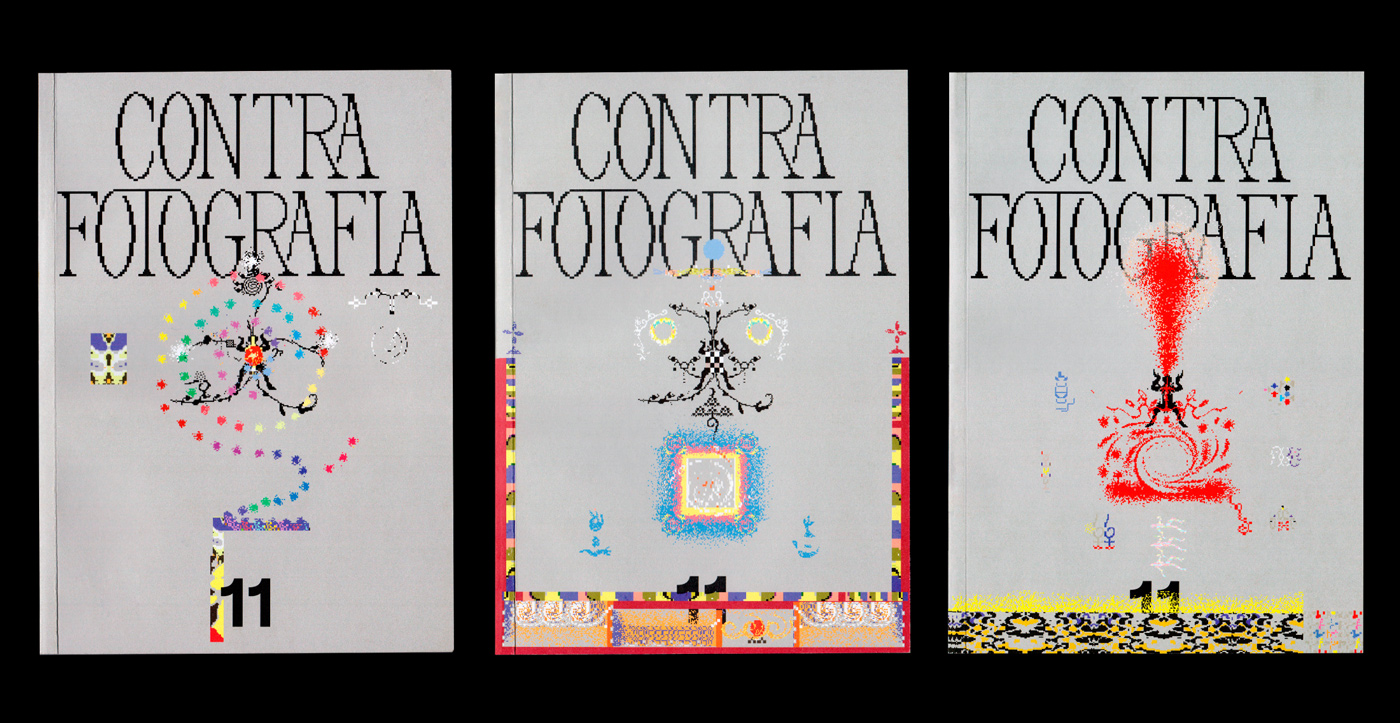

From all your amazing issues, Contrafotografia #11 has caught our eye! Can you tell us more about its design and how it translates its theme?

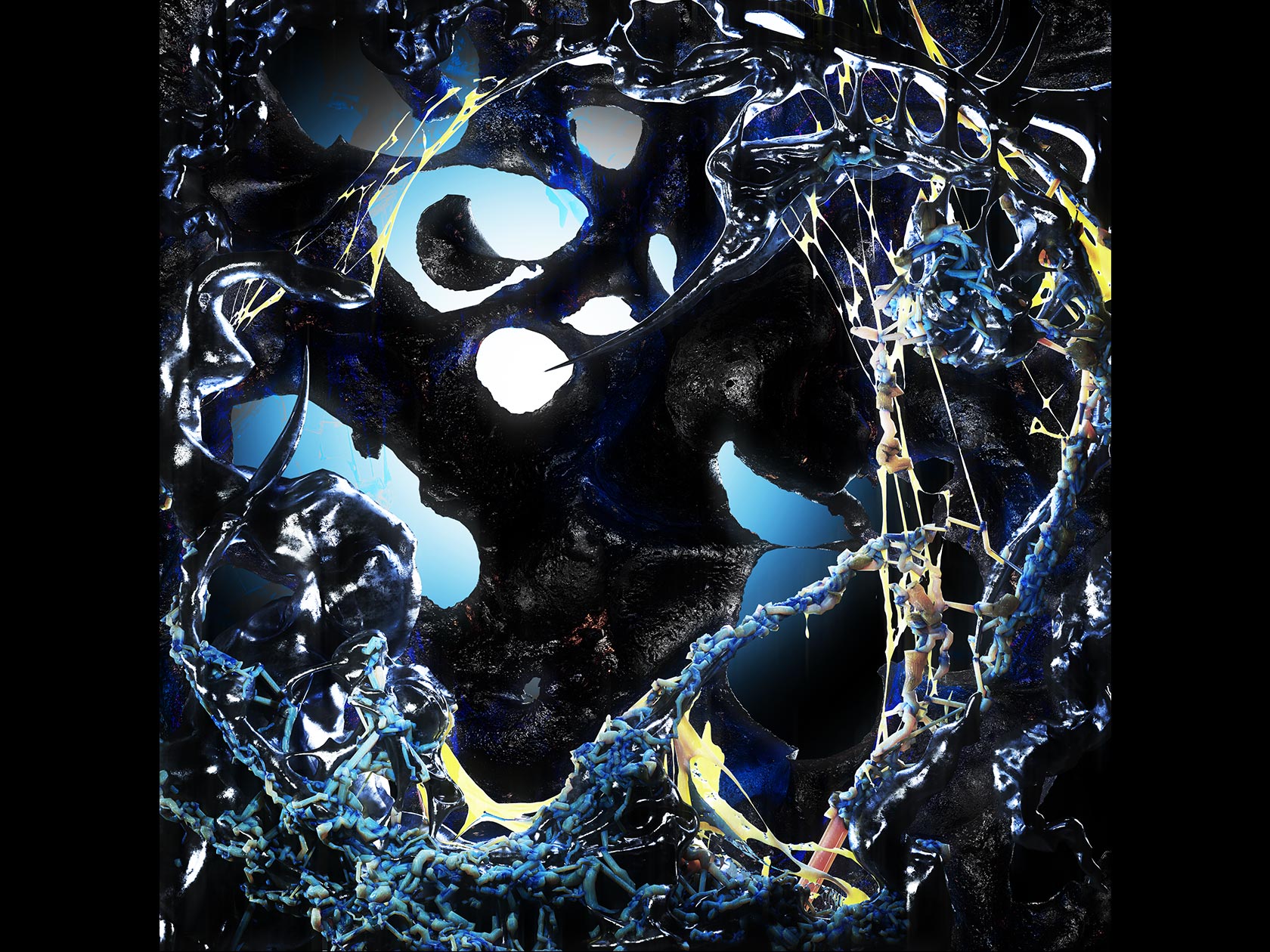

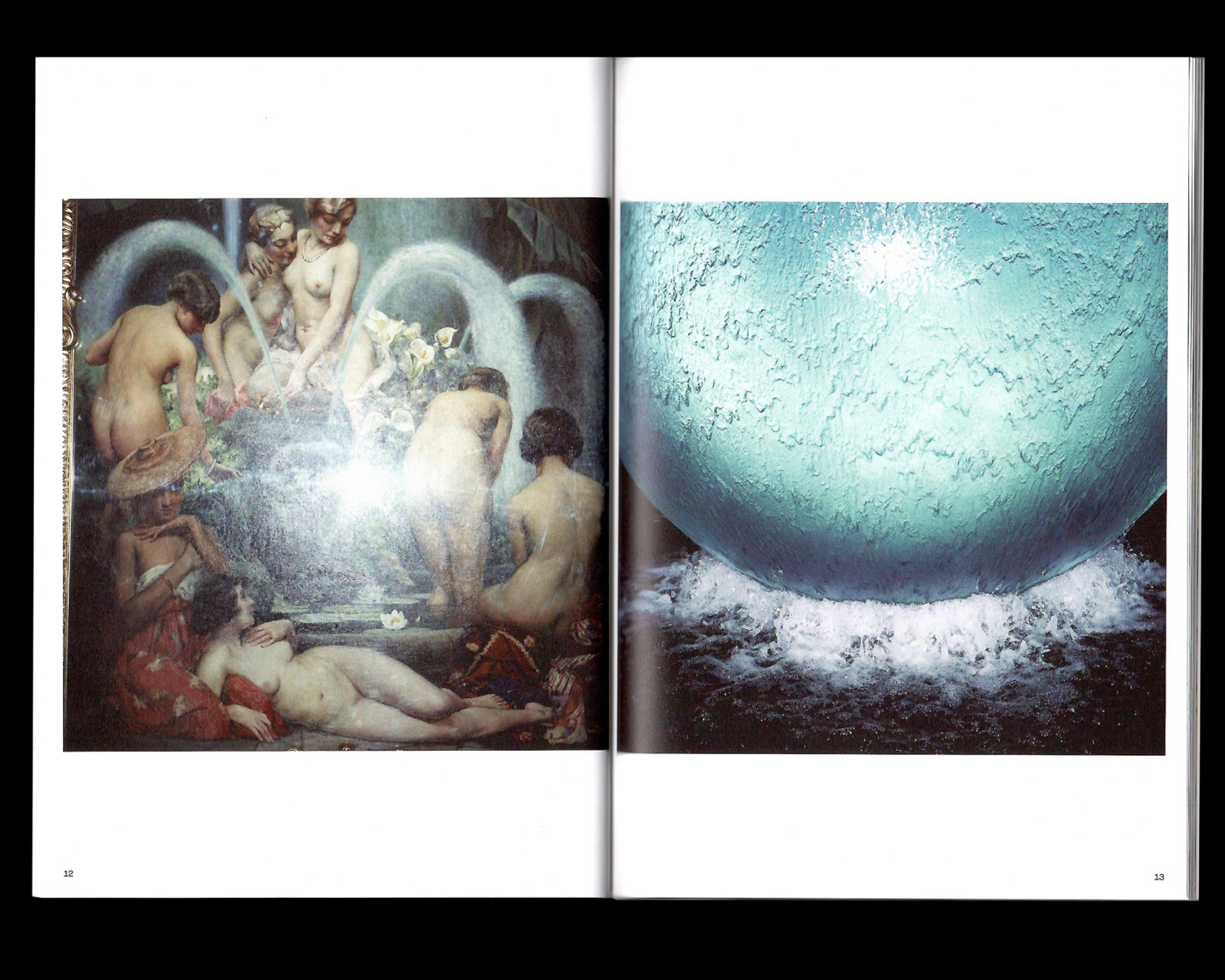

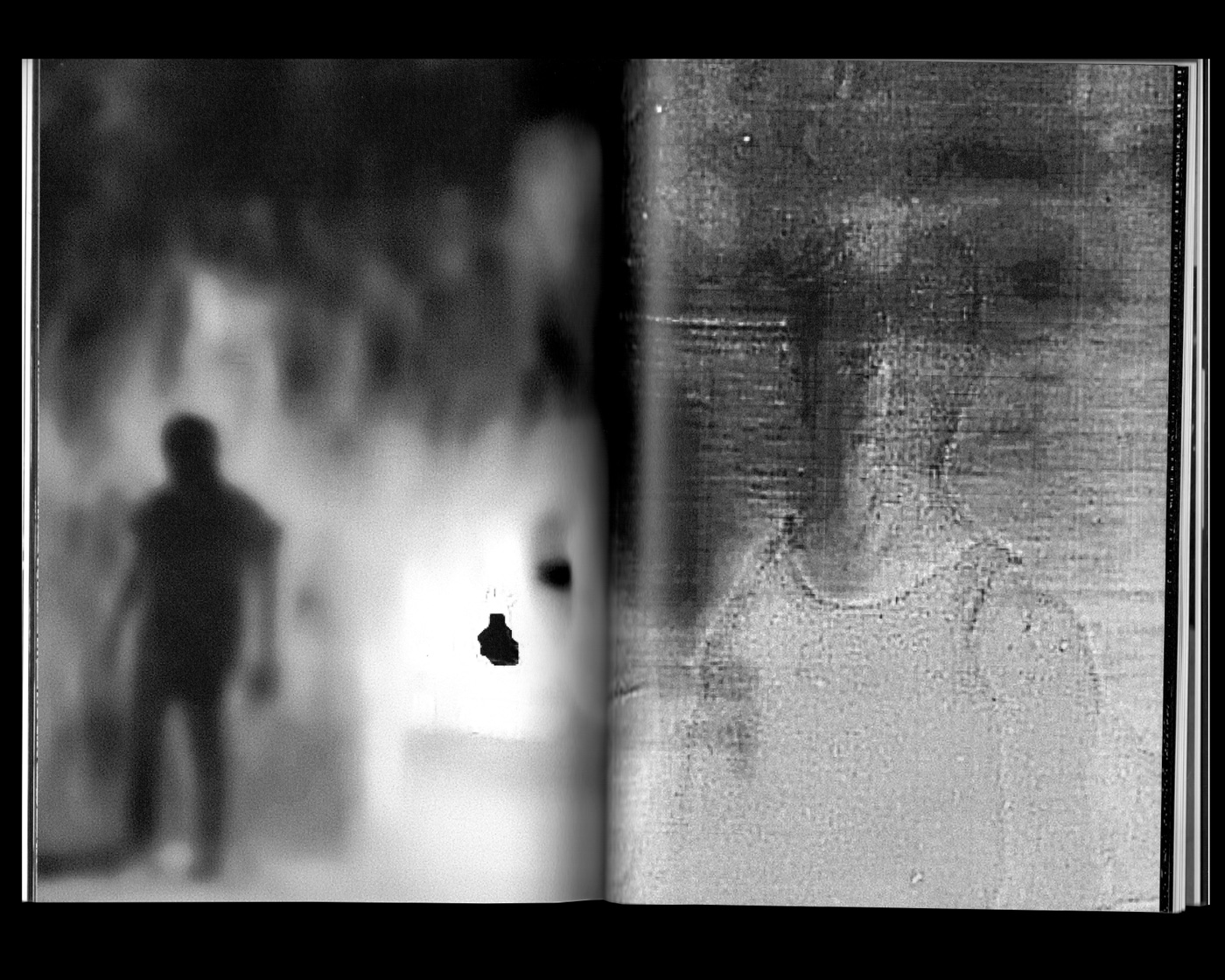

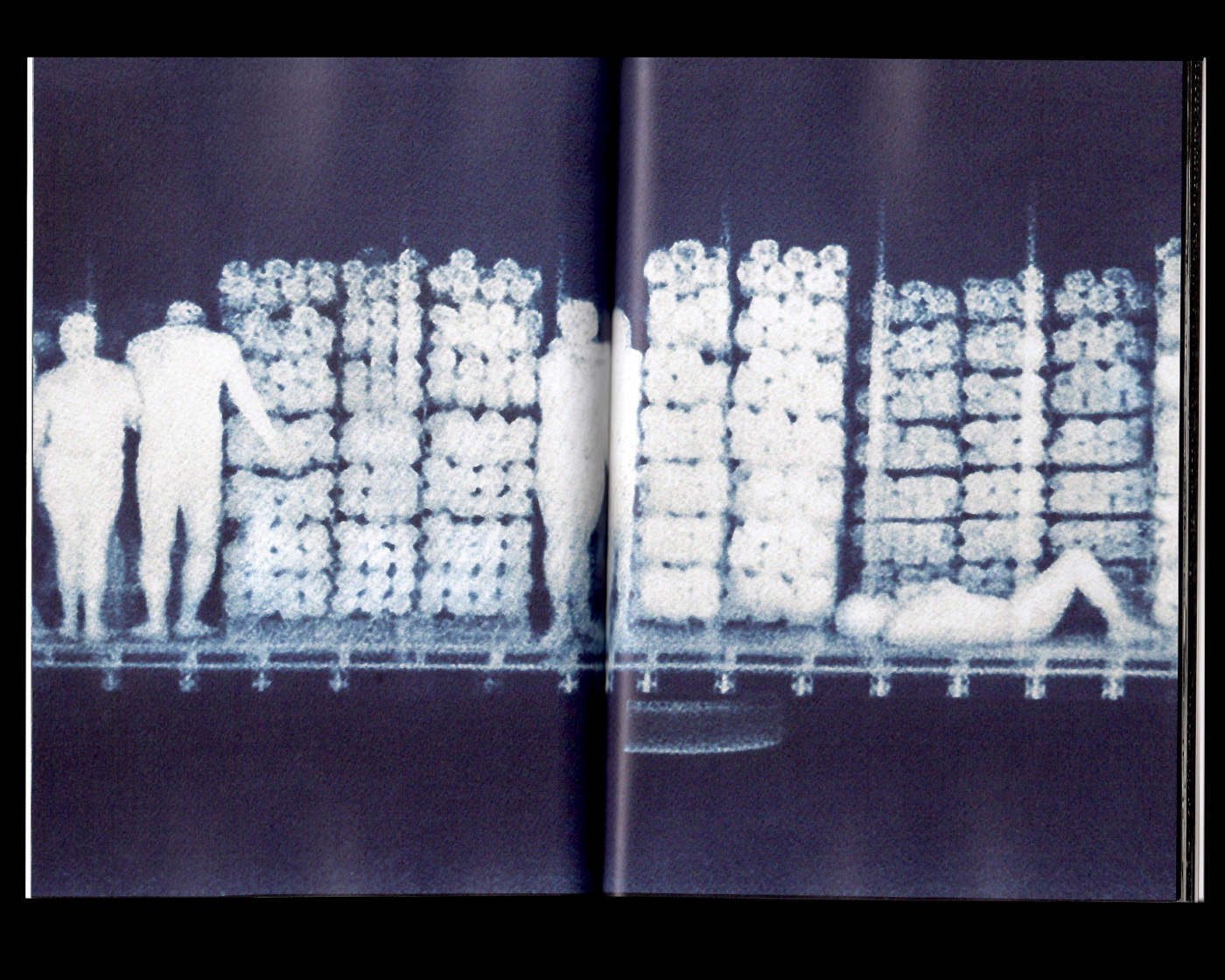

The project aims to offer a new perspective on the context of the audio-visual surplus that we inhabit. It suggests that perhaps the problem is not only the saturation of images but also the homogenization of the visual content we consume. It investigates our disconnection with images and new connections that might emerge from it. It seeks to renew our relationship with images and to mobilize their creative and representative forces. “Realismo Digital” offers a contemporized, dissident, and committed documentary on our digitalized reality.

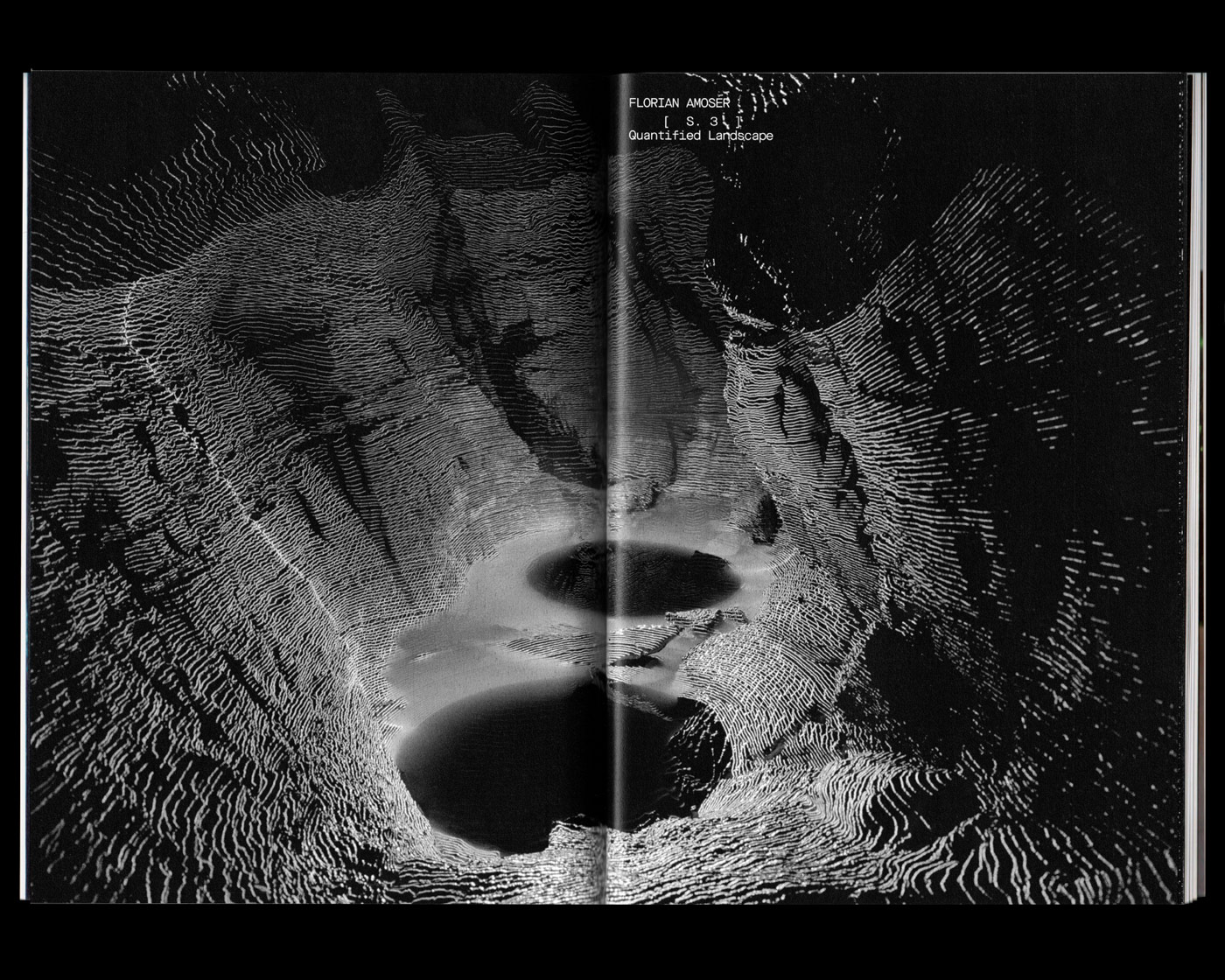

For this issue, we wanted to present the images in a simple way, not too saturated and on a white background, to draw the reader’s attention. Reading the issue should feel like an immersive experience. The photographs are separated from the texts at the end of the publication. The layout doesn’t follow a rigid column layout and is made by code, connecting with the idea of creating new languages through new technologies.

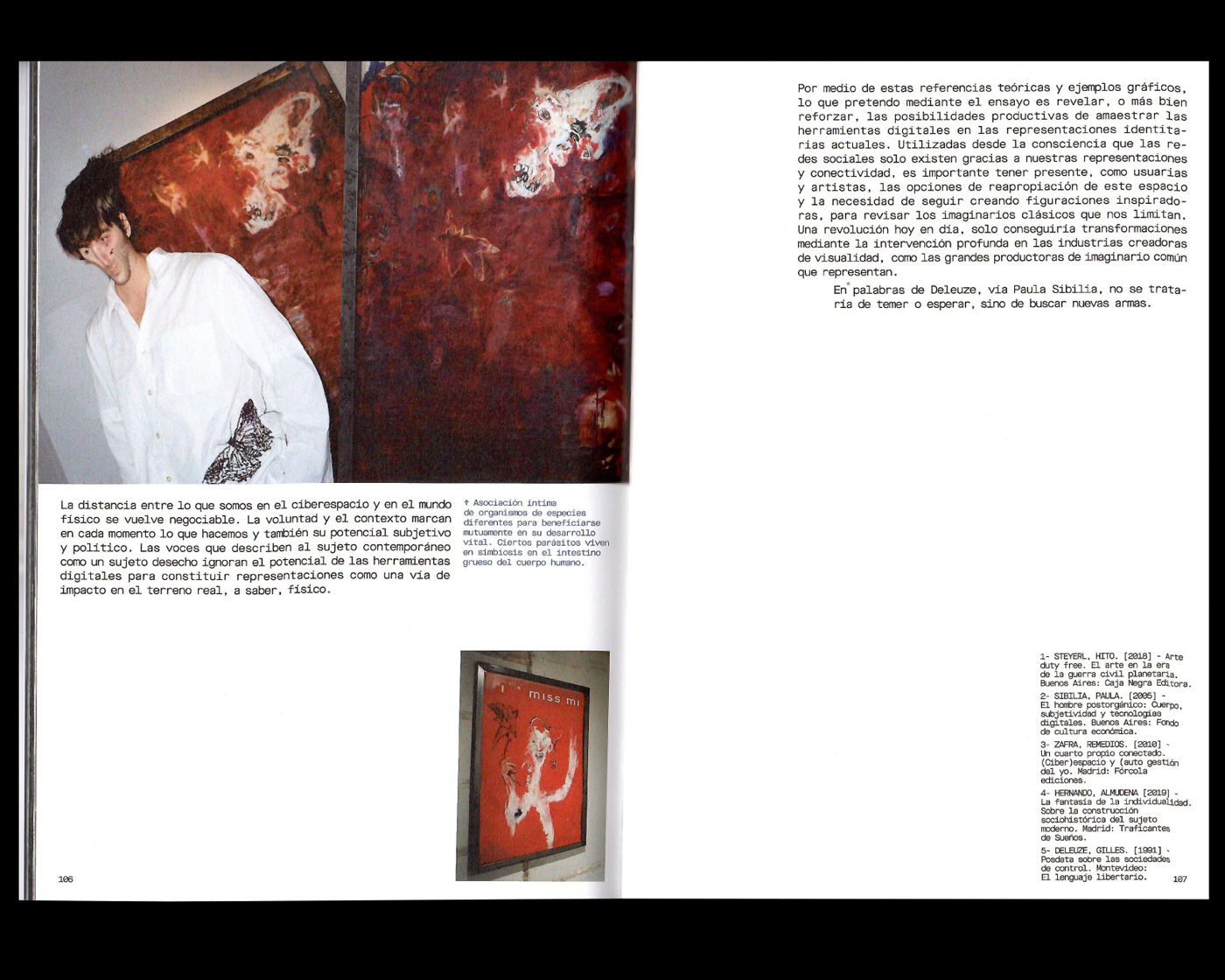

The publication presents photographs by Julián Barón, Nicolás Combarro, Noelle Mason, Antonio Julio Duarte, Miguel Ángel Tornero, Mayra Martell, Andrea Soto Calderón, Wally Walter, and Florian Amoser. It includes the article “Autopaparazzi: Posibilidades performativas del yo digital” (Autopaparazzi: Performative Possibilities of the Digital Self) by Natàlia Montardit, interviewing Lara Joy Evans, DJ Lostboi, Juaki Pesudo and Matthieu Croizier.

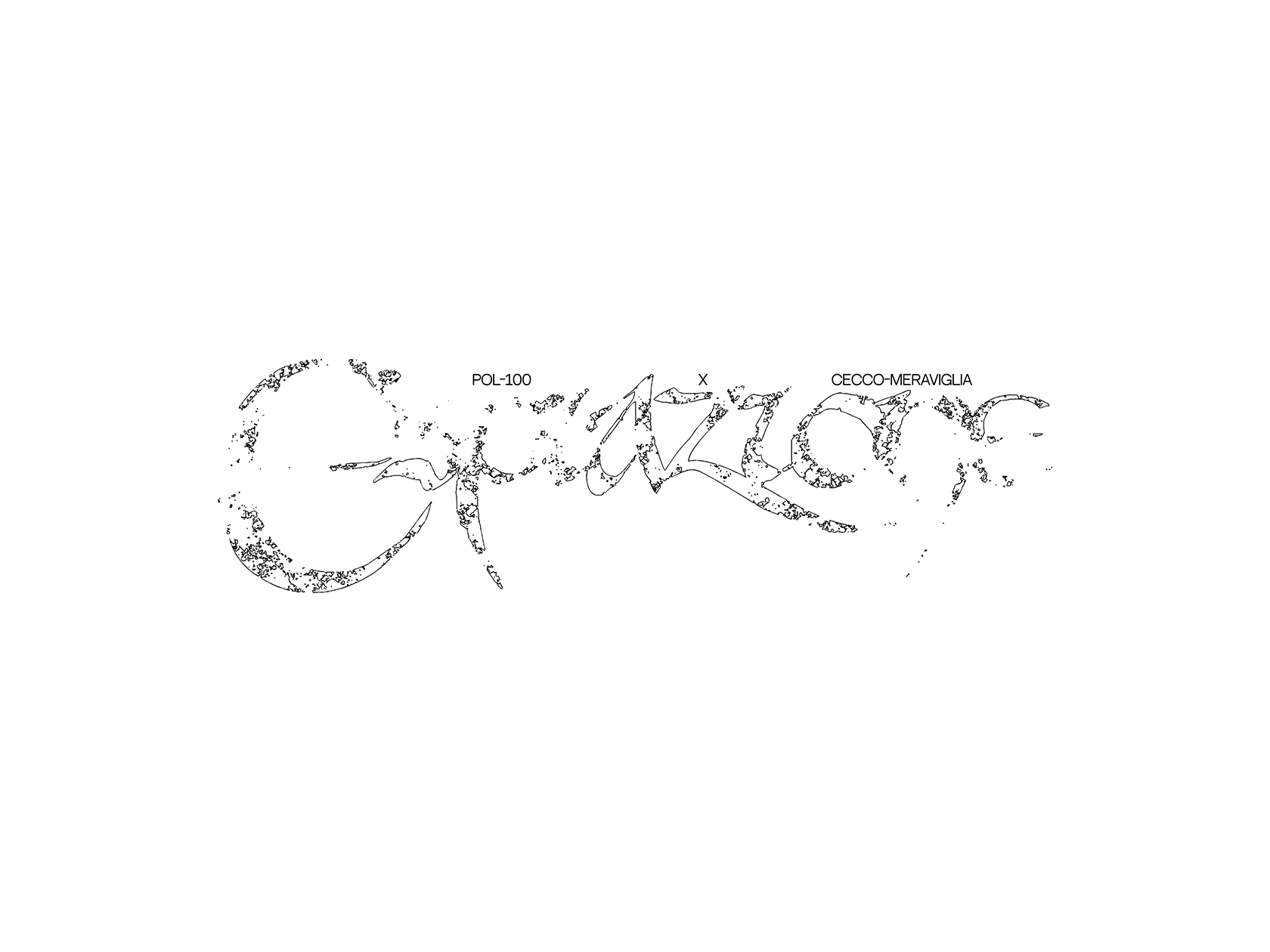

The cover typography was designed by Lluis Domingo, a friend of Marta from university, and for the different illustrations of the cover we had the pleasure of working with Somnath Bhatt.

As a photography magazine, what role does text play in your visual explorations? What is your font and layout policy (if there is one)?

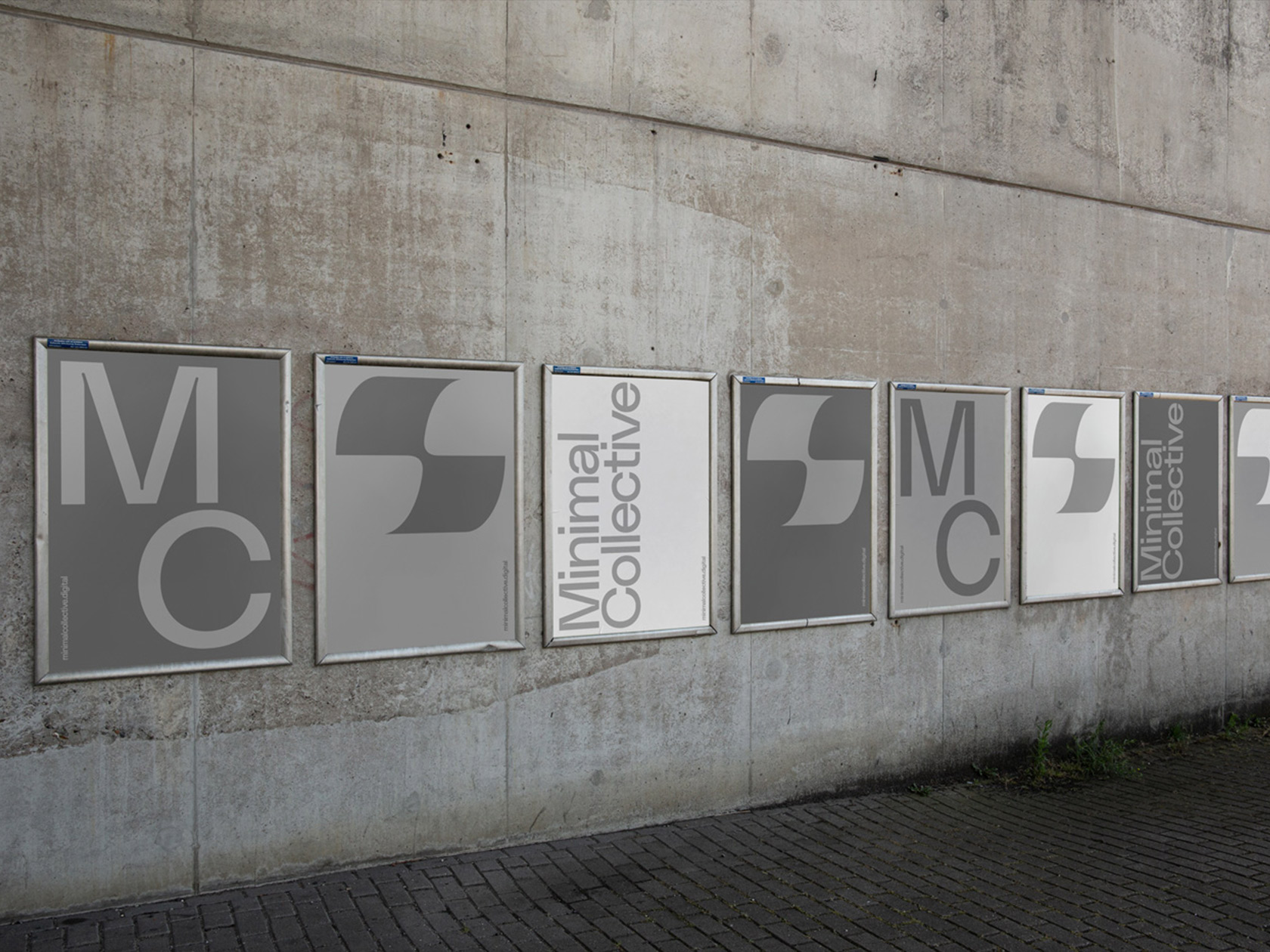

When Gonzalo joined the project, he suggested that each issue should have a personalized lettering based on its theme. There are fixed design elements, such as the numeration on the spine, but the wordmark of the magazine is always changing. It’s either made by our designers, the cover illustrator, or one of our colleagues.

As for the typography, we usually use system typefaces, as they are accessible and public domain. This choice is very much in line with the whole concept and principles of the project.

Another vector of your publishing activity is Roca Negra. How is it different from Contrafotografía? Besides, why is it called so?

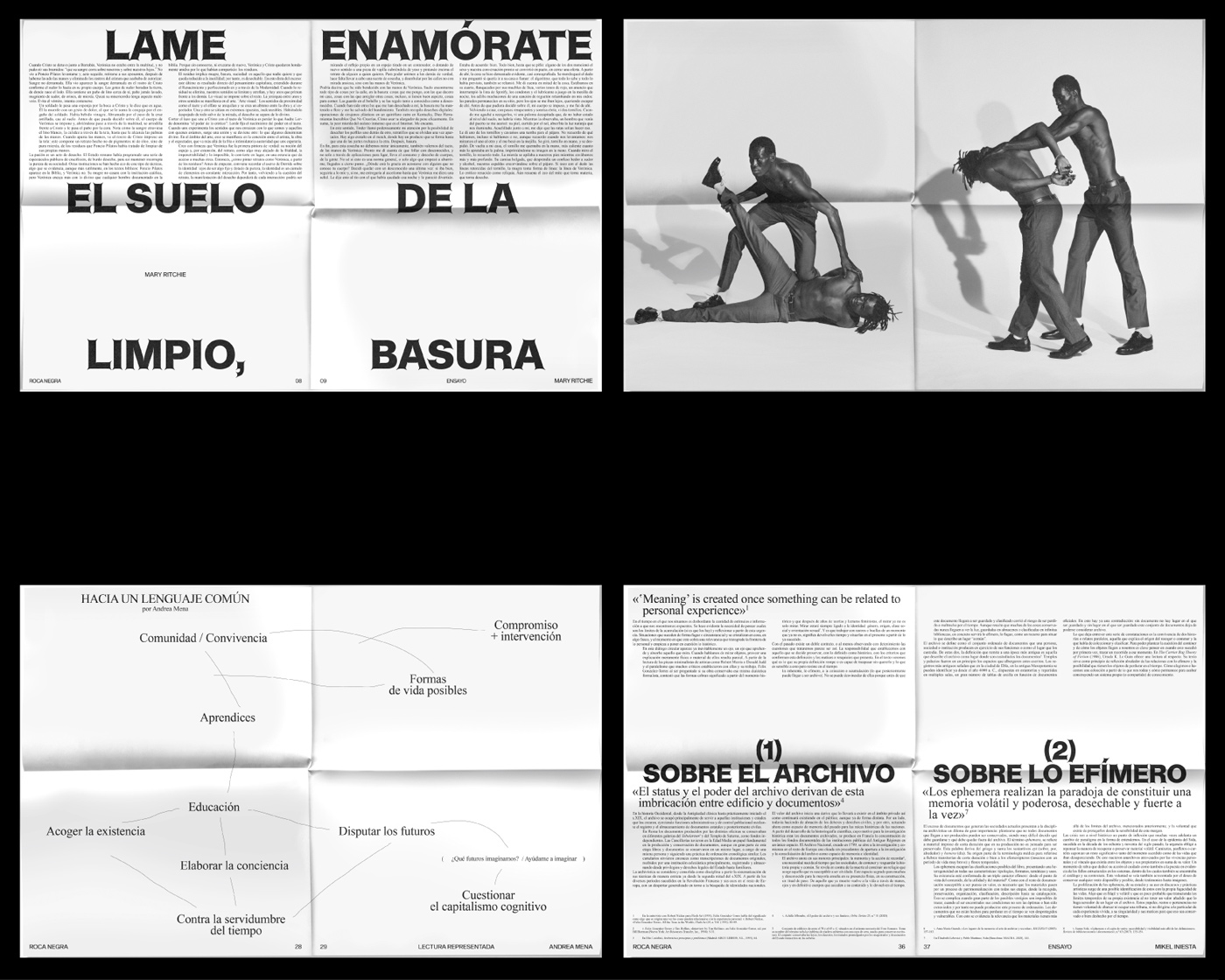

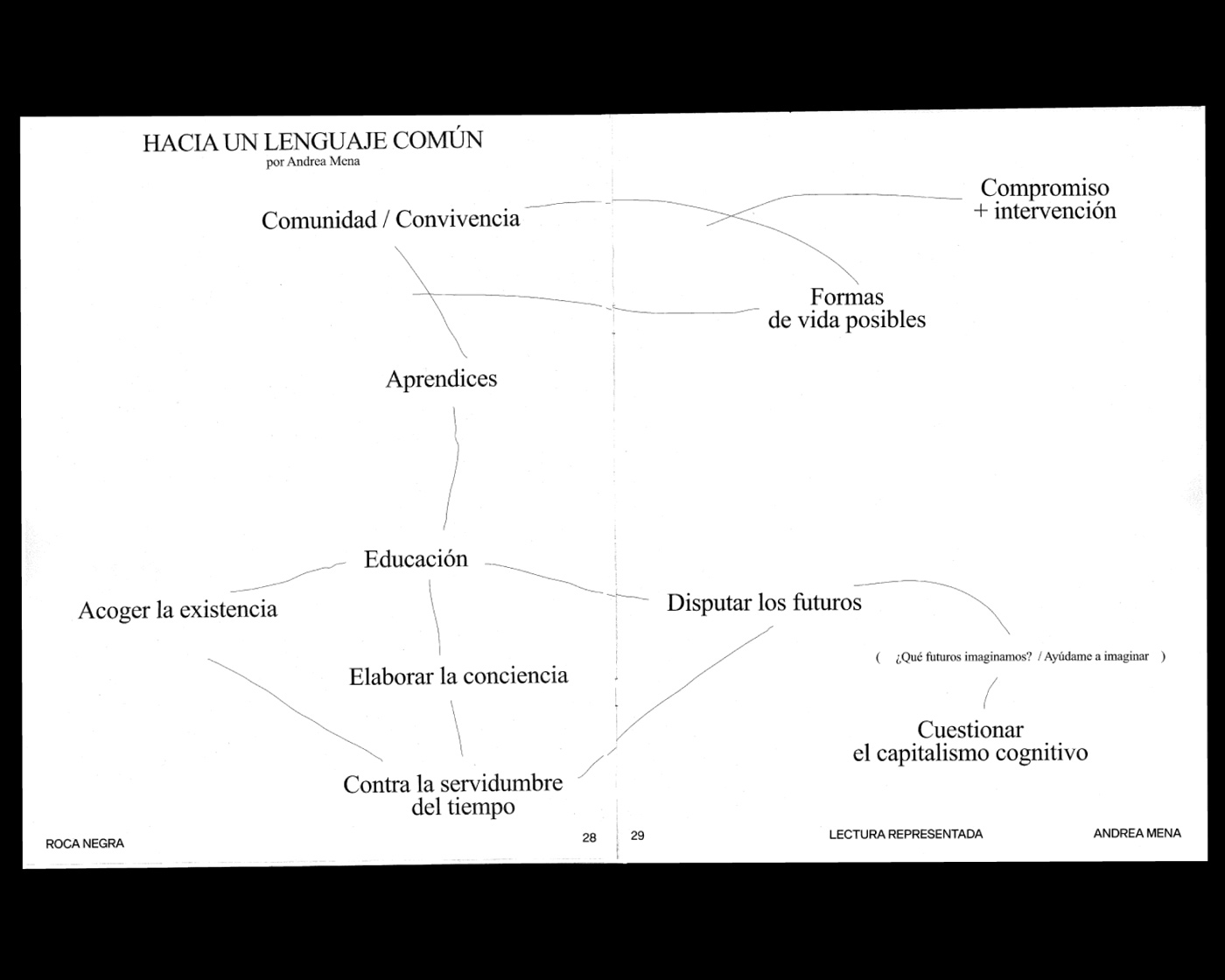

Roca Negra (Black Rock) is a beautiful spot in the mountain next to the State Park of Garraf, in Castelldefels. This magazine is a counter-cultural space for ideas of all kinds. In contrast to Contrafotografía, it comes in a newspaper format and consists mostly of text contributions.

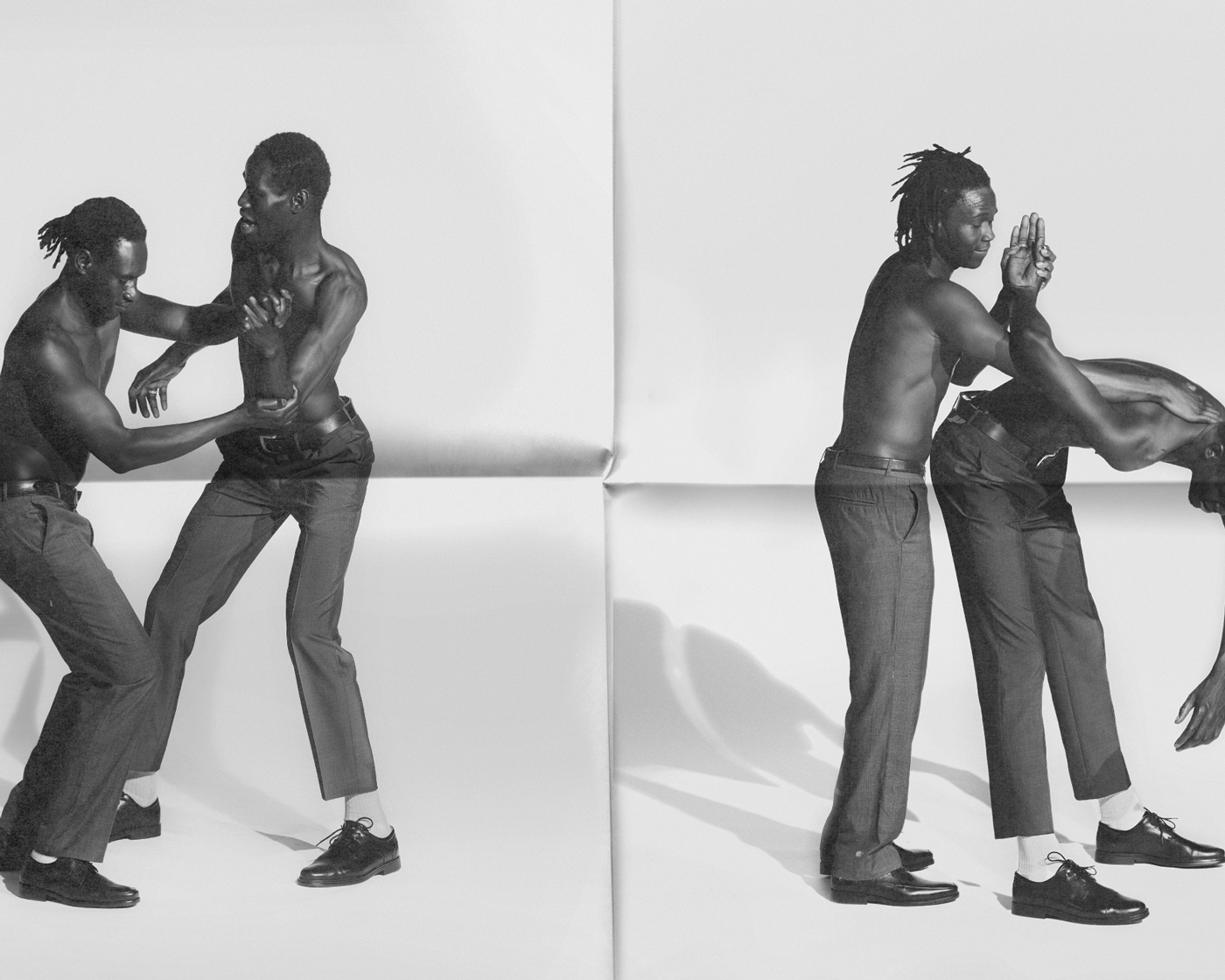

Each issue of “Roca Nega” includes a documentary photographic series related to the texts—a subtle connection to “Contrafotografía.” In the latest issue Roca Negra #2, the texts are accompanied by the photographic series “Reduction” by Felipe Romero, exposing the “Manual de Defensa Policial” (Police Defence Manual) and showing the discriminatory practice of the police.

You’ve recently hosted your first exhibition with the photographer Émilie Désir. Could you elaborate on this new experience and give us a brief sum up?

The Ateneu l’Harmonía in Sant Andreu asked us if we wanted to do any activity outside of meetings in dark, lonely rooms. We weren’t sure about it at first, but Émilie is a good friend and has worked with us before, so we decided to ask her about the recent protests in France. A long time ago, with the first money we saved from selling out the first three zines, we bought a couple of cheap frames for exhibitions. We haven’t used them in ages, so this was a good excuse to hang them on some white walls.

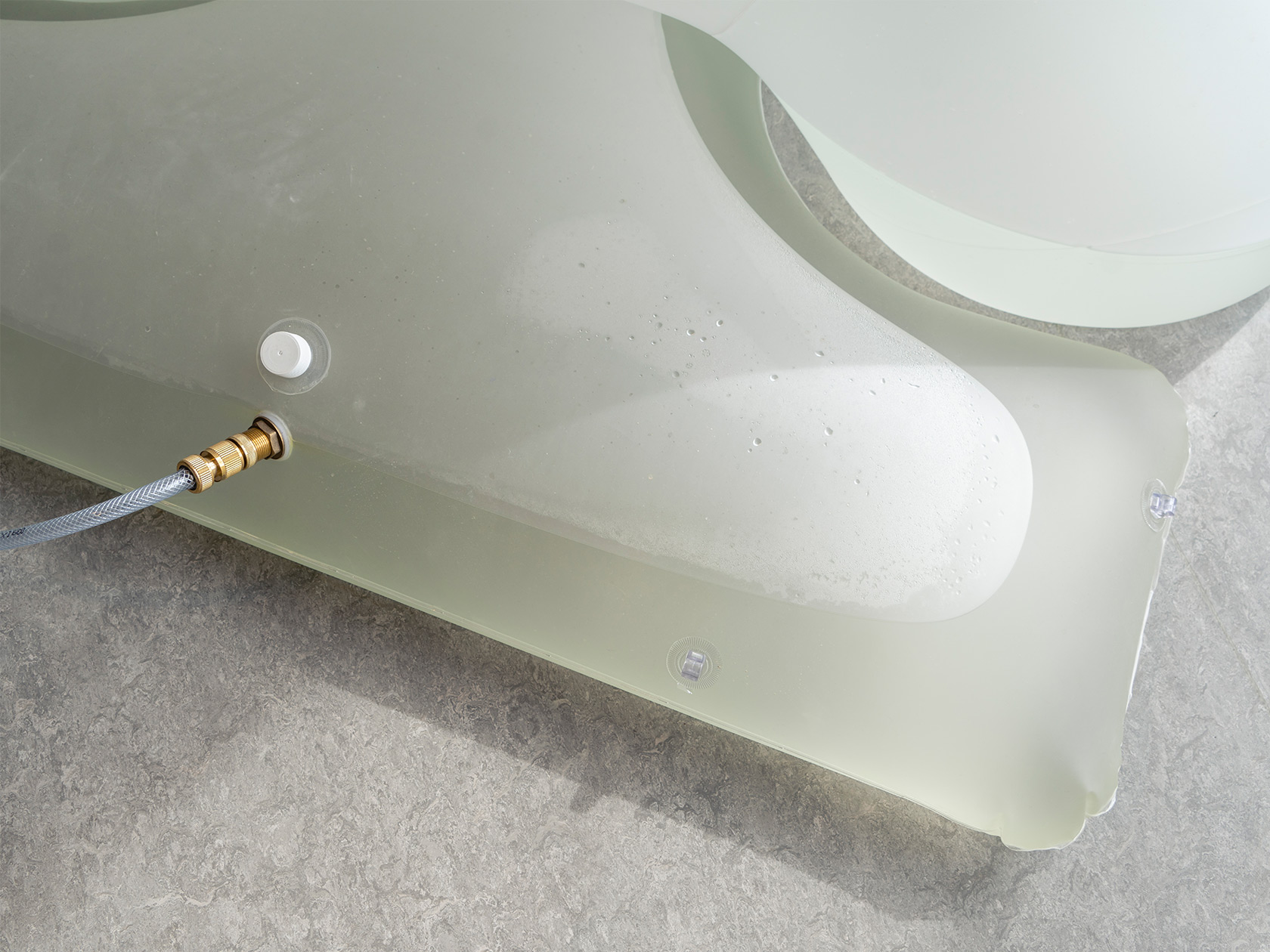

Émilie sent us a series of photos she took at Saint-Soline, where there was a massive protest against huge water pools filled with underground water. Since the South of Europe is suffering from a widespread drought, the irrigated lands available are impossible to maintain. To keep this exploitative system of the land going, the government decided to dry out the underground with these pools, risking an ecological crisis. The exhibition received some nice feedback, as it’s the same situation in Catalonia where our water reservations are around 25% and millions already have water service cut at certain hours.

We hope we can do more exhibitions soon! Since the Ateneu l’Harmonía is a popular space, people of all backgrounds pass by, which is probably the best way to make photography available to everyone in a DIY way.